Preserving Our Environment: The Battle for Estero Bay

While doing research for Lost Icons, I came across a quote in the News-Press that I have cited several times in other articles and presentations. Written in the late 1970s, this quote seems to bring the past and the future together quite nicely: “Nobody really wants to stop progress, but there is an increasing awareness that the island is in danger of becoming a polluted paradise.”

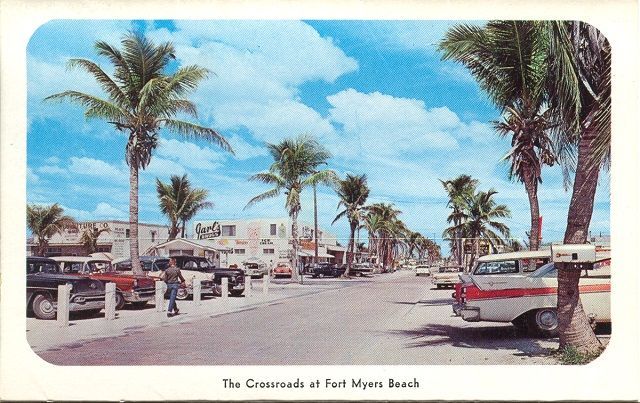

Over fifty years ago, the paper stated that Fort Myers Beach was at a crossroads. The 70s were a time of rapid, uncontrolled development with over 68 condos being developed in a single decade. This led residents to vote to incorporate the town so we could control our own destiny and stop the over-development of our island. The newly born town elected its first town council who worked very hard to create a comp plan that would guide our development and preserve our island lifestyle.

This plan was completed in 1995 and had served us well until Hurricane Ian damaged every building on the island. Now that we are in the rebuilding mode, we are once again at a crossroads: Do we stick to the comp plan and turn down the developers who want to build higher and bigger? So far, the council has been carefully considering all arguments and is making logical decisions trying to keep as close to the comp plan as possible.

The council and residents need to tread carefully to make sure, in our efforts to build back, we spend time anticipating the unintended consequences of building back bigger. One very good example of this is the recent attempt of two legislators to take back 225 acres that are part of the Estero Bay Aquatic Preserve. (More on this in another post).

This was not the first time our beautiful back bay was threatened. Let’s go back to the 1960s when a group of concerned residents decided to take action to preserve the beauty of our back bay.

Back to the Future

The uncontrolled growth of the island in the 70s gave way to a new wave of environmentalism in the 80s. One of the most important environmental wins was the creation of the Estero Bay Aquatic Preserve. It is important to understand the history of the preserve to appreciate its importance to our future.

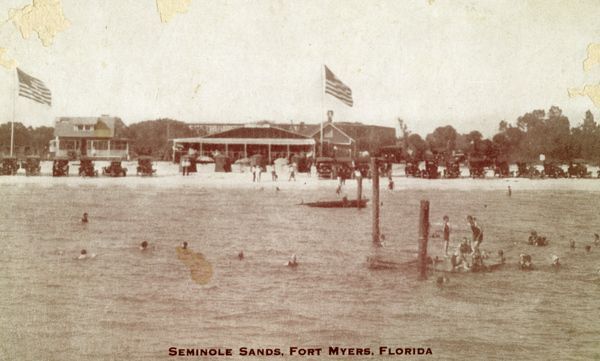

It all began as early as 1958 when Barry C Williams and investors purchased 5,500 acres of land along the northern and eastern coast of Estero Bay for $1.6 million. The developers had big plans to create a seawall along 18 miles of coastline. The seawall would “straighten out the jagged coastline by using 17 million cubic yards of fill.” It would also swallow up 1,100 acres of land that was previously underwater. A 12-foot channel would be cut through the seagrass beds around the seawall. This technique had been used in Tampa, St. Pete, and Sarasota which turned the most productive estuaries in the state into barren wastelands.

When the residents got wind of this plan, they went into action. They realized that Estero Bay was not as pristine as it had been in the past. Fishing was not as good as it used to be; the water was not as clear as it should be; seagrass beds were dying and affecting marine life. This group formed an organization known as the Lee County Conservation Association back in 1961. The idea caught on and it did not take long for the membership to include more than 50 percent of the county’s registered voters (Miller). At this time, the organization did not have the support of the county commissioners who were more interested in growth and development than the environment.

Edited in Prisma app

Most of the group’s members were believers in private property rights. They did not want to see their fishing grounds destroyed because these grounds belonged to the public. Before this group was formed, it was not unusual for developers to cut down mangroves to create waterfront communities with little pushback from environmentalists.

Although residents tolerated the local developers, they were becoming more and more concerned about the long-term effects of this practice. They realized that without protection, Estero Bay would be ruined, and Williams’ proposal would put this destruction on a much larger scale. The members of the association began a campaign to save the bay. They wrote letters, spoke with politicians, and used their voting block to change the county leadership.

The association argued that the submerged lands belonged to the state. They wanted to create the Estero Bay State Park. This was a solid argument since the law clearly states that any land above the high tide mark can be owned privately. However, any land below the high tide mark belongs to the state. Eventually, the association’s work paid off and led to the creation of the first aquatic preserve in Florida. This became a model for the 41 other preserves that were created along the state’s coastal waters.

New Preserve Threatened

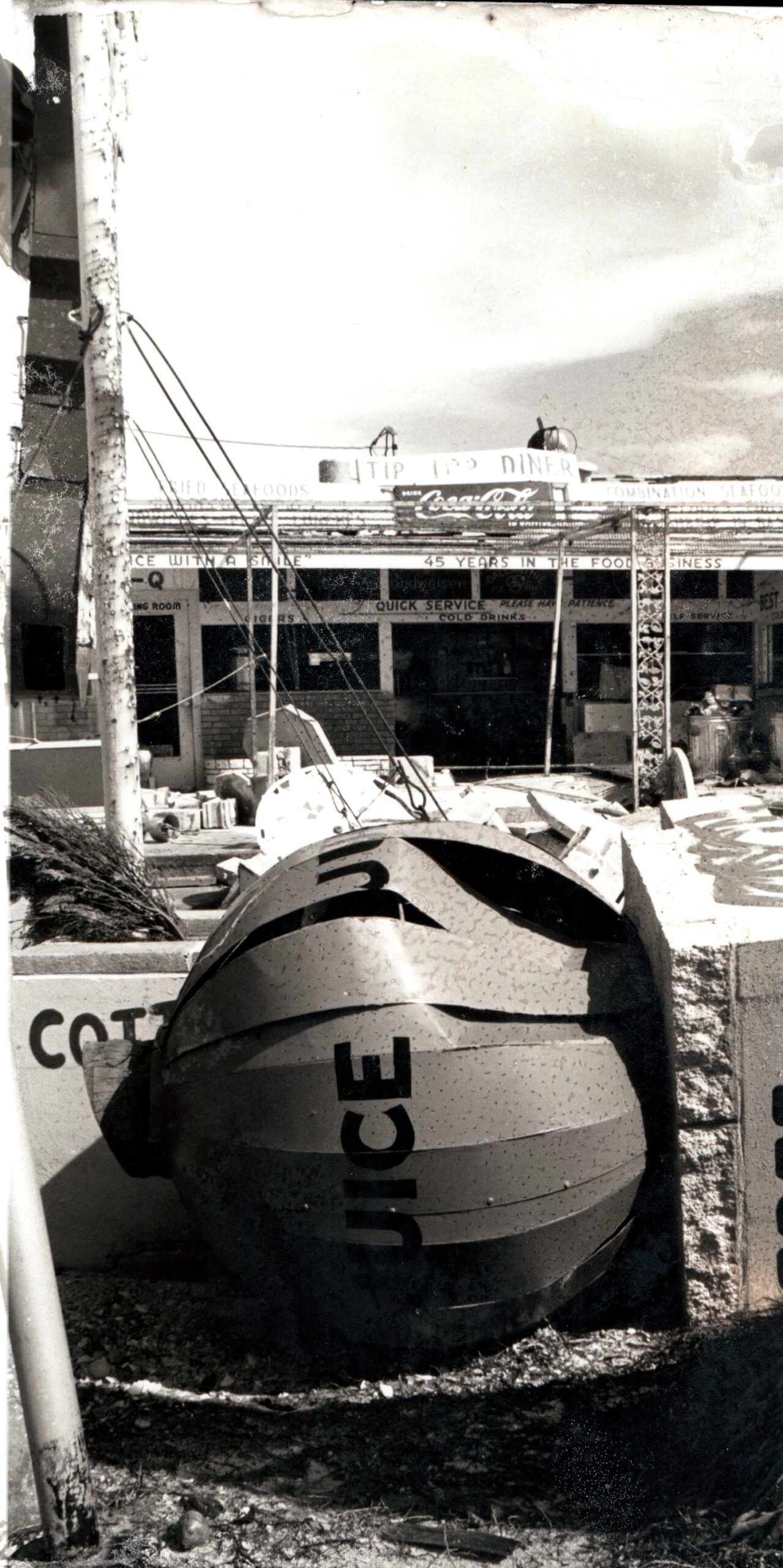

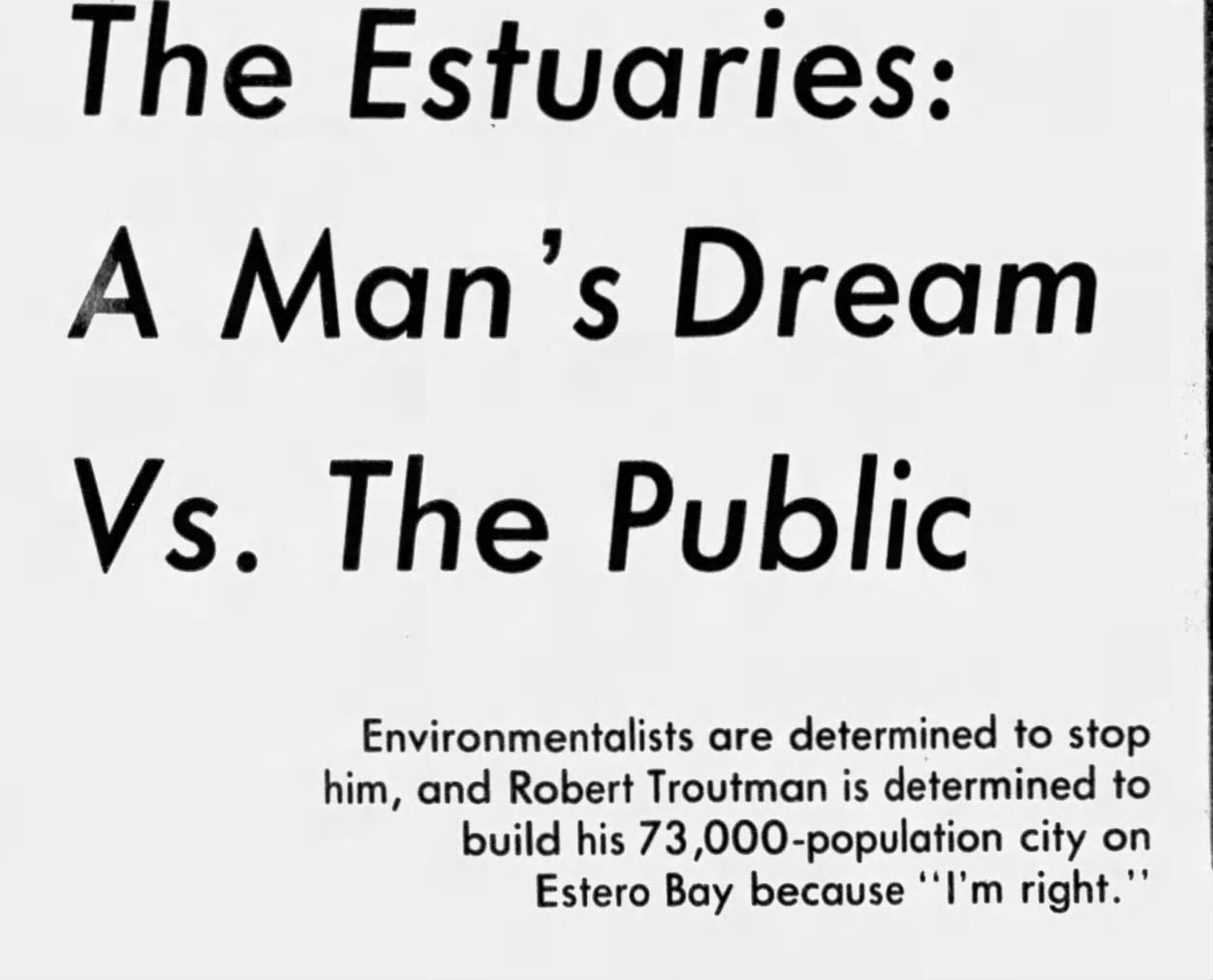

This is paragraph text. Click it or hit the Manage Text button to change the font, color, size, format, and more. To set up site-wide paragraph and title styles, go to Site Theme.Although the group was successful in creating the preserve, their battle was not over. In 1974, Robert Troutman, who was the attorney for Williams, brought forth his plans to create a development known as Estuaries. Troutman had plans to build a city the size of Fort Lauderdale along the coastline from Punta Rassa to Hendry Creek. His development was to be home to 78,000 people, included five different villages, three golf courses, 14 tennis centers, four marinas, 24 lakes, and 403 acres of parks. Ninety percent of the land for the intended development was considered wetlands.

This is the same Troutman who, sixteen years earlier, represented Barry C. Williams and his investors who purchased the 5,500 acres along the northern and eastern coast of Estero Bay for $1.6 million. Robert Troutman was a heavy hitter from Atlanta who was friends with the Kennedys and the Rockefellers.

When the Lee County Conservation Association learned of Troutman’s plan, they decided to take on him and his team of lawyers and developers.

Environmentalists realized what Troutman’s planned development would do to the delicate ecosystem surrounding Estero Bay. They knew that if this ecosystem were to collapse, it would devastate our marine life as 95 percent of all marine life spend a part of their lives in an estuary.

This association was up against more than just Troutman and his high-powered staff. They were also pitted against the Lee County Commissioners who were more interested in the money they could make off this development than in the environmental impact it would have on the bay.

Eventually, the association was successful in electing commissioners who cared more about the environment than development. Troutman needed 3 votes to approve his development plan and in six years, he could not receive approval. The newly elected commissioners were too concerned with the long-term environmental effects of the project, and many had friends in the environmental community.

Troutman continued his fight in the court feeling confident that he would win with his team of biologists and lawyers. The association believed that the development would be denied since the area to be developed was in the newly created Estero Bay Aquatic Preserve.

After several years, Troutman was finally defeated in court when the battle to stop the project went all the way to the Supreme Court. He couldn’t believe that the people of southwest Florida were not embracing his dream of a community on the shores of Estero Bay. In fact, Troutman was later found destroying mangroves in an act of retaliation.

Even though Troutman did not see his dream come true, he did continue to develop on Fort Myers Beach acquiring Sandpiper Cove, Siesta Isles, and Bay Beach. But he did not destroy our bay.

Now, over fifty years later, legislators are once again testing the waters to see if they can carve out over 200 acres of the preserve so that a 300-slip marina can be built near the shrimp docks. More on this in my next blog post.