Fort Myers Beach History Spotlight: Hugh McPhie

This is the first in a series of stories I plan to publish celebrating the individuals that have shaped our island’s history over the past 200 years.

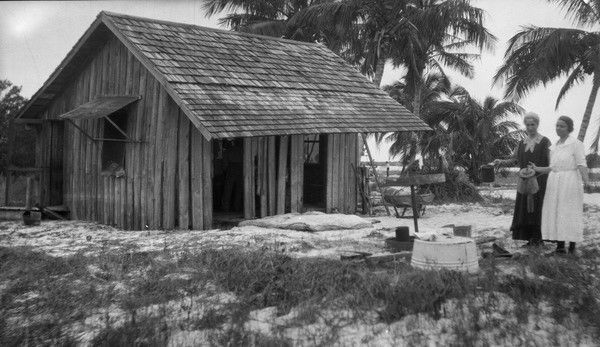

This is a typical homesteader’s cottage in the late 1800s on Fort Myers Beach.

For the most part, in the late 1800s, Fort Myers Beach was uninhabited except for a few brave souls who decided to take advantage of the Homestead Act of 1862. This act allowed the head of a family (or any person over the age of 21), to claim as much as 160 acres of public land. In order get a title to the property, the homesteader had to live on the land (called “proving the claim”) and cultivate it for five years.

It took until 1875 for the island to be platted which enabled the deeding of properties. Therefore, those few people who lived on the island prior to 1875 were not legal homesteaders; rather they were referred to as “squatters.” However, if a person were to live on a property for six months, he or she could pay cash for the land and receive a title. The going price at in the 1870s was $1.25 per acre.

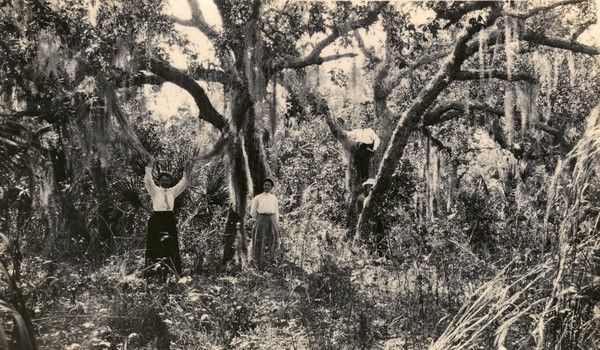

Most homesteaders who lived on the island built primitive palm-thatched log homes (cheekees). They were isolated from the mainland, since the first bridge to the beach was not completed until 1921. Because the island was made up of thick patches of saw palmettos and mangroves, there were no roads, and the only way to get around was by horse or boat.

When the early homesteaders lived on the island, they were surrounded by saw palmettos, oak trees, and mangroves.

One of the earliest homesteaders on the island was a man named Hugh McPhie. He arrived in America from Scotland in the late 1880s and, in 1899, McPhie was granted the third patent on the island homesteading 112 acres running from Flamingo Street to Fairview Isles (the first patent went to Robert Gilbert, and the second to Albert Austin). In 1907, McPhie proved his second claim which ran from Aberdeen Street to Avenida Pescadora and to the end of Seminole Way.

According to Jean Matthew, in her book, We Never Wore Shoes, McPhie was considered the “island hermit” back in the 1920s and 1930s. McPhie’s story is a tragic one. He left Scotland after his wife died in an epidemic leaving his two young sons to live with his sister. His original plan was to come to America, find a new wife, and then send for his children.

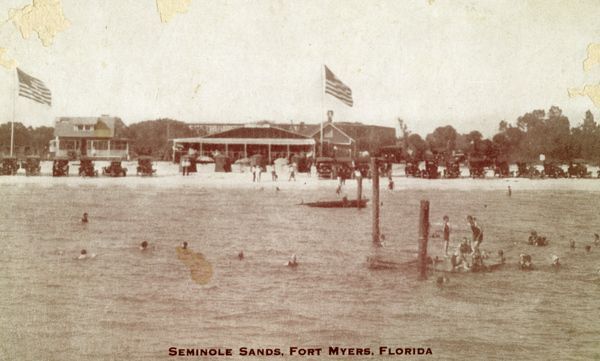

Eventually, McPhie discovered Fort Myers Beach which was the perfect place to be alone in his grief. Matthew reports that, “Hugh lived alone in a fishing shack near the south end and managed to cultivate a garden and catch enough fish to make out a living.” The old McPhie homesite was situated in a beautiful coconut grove just south of what is now the Outrigger Hotel.

Since there were no stores on the island at that time, when he needed supplies, McPhie would row his boat over to Sanibel where there was a small store and a post office.

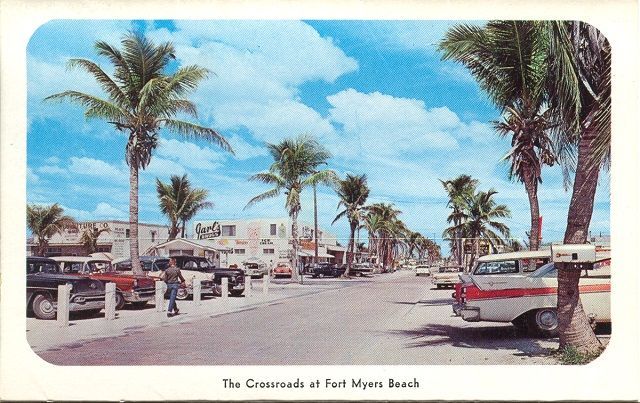

McPhie loved living on the island and resented the “development” that he thought would ruin the life he knew so well. For many years, he refused to give in to developers who were trying to purchase his land. However, in 1938 he finally surrendered and developed a tract of land known as McPhie Park (from Aberdeen Street to Avenida Pescadora and to the end of Seminole Way).

According to Rolfe Schell in his book, History of Fort Myers Beach, McPhie held on to his properties longer than any of the other early homesteaders. At one time, during the 1920s real estate boom, McPhie was offered half a million dollars for his land, but he turned it down. He cared more about the land than he did the money. Once he subdivided McPhie Park, he sold many lots in the park and most of his original homestead for forty thousand dollars (Schell).

Shortly after selling off some of his land, McPhie returned to his home country for the first time in 50 years to find his sons had grown up and were now old men like him. McPhie only stayed in Scotland a few weeks. His sister came to live with him once he made improvements to his shack. She stayed with him until 1942 when he was found dead on the beach. His homesite was destroyed in the 1944 hurricane.